Latest

The historic Hotspur Press building on Manchester’s Gloucester Street

The Holy Orange and the Messiah of Clacton Pier

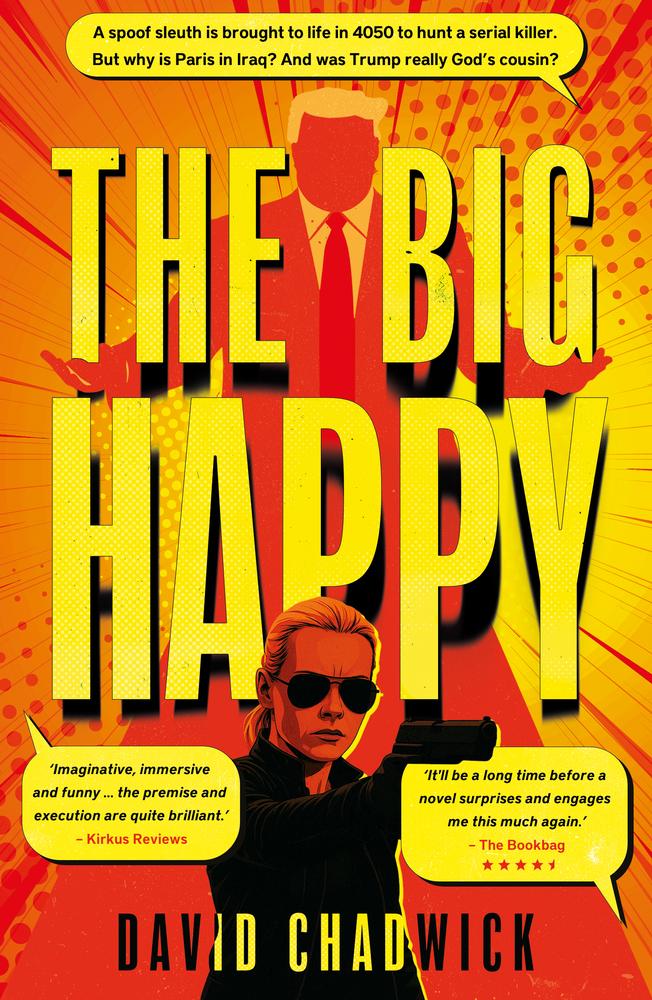

The Big Happy is my most ambitious novel and the first written because I believed it needed to be.

This isn’t intended to sound pompous because The Big Happy doesn’t take itself too seriously, even though it addresses serious concerns. It can be read as a dystopian satire, a crime noir thriller, a black political comedy, or all three. It was a joy to write and is meant to be a fun read.

Like many dystopian novels, The Big Happy owes a lot to 1984 and Brave New World. Huxley’s ironic title is taken from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, in which the heroine Miranda speaks the line, ‘O brave new world, that has such people in it!’ Correspondingly, my protagonist is called Miranda, although she isn’t nearly so impressed by the people in her new world. You will also find an homage to Huxley’s breathtakingly elegant editorialised passage, with Henry Ford replaced by right wing British politician Michael Gove, along with many other references to Brave New World, right up to the concluding coda.

The Big Happy is also indebted to another classic dystopian novel, Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange. Burgess’ fictional street speak, ‘Nadsat’, brilliantly evokes the mindset of his narrator, Alex, and the youth gang culture that thrives on ‘the old ultra-violence’. Similarly, I wanted a dumbed-down argot to reflect the shallow and faddish culture of PopRep, resulting in IngoLingo, an infantilised rendering of English that uses only short or catchy words – a kind of Nadsat passed through the lens of social media.

It's been said that Orwell feared we will be destroyed by what we hate; Huxley by what we love. But what if we are destroyed by what we are? By what we cannot help but be?

The first quarter of the 21st Century has presented an existential threat to the existing global order, especially in the western democracies. If you haven’t guessed, I’m talking about digital technology and in particular, the ubiquitous and corrosive impact of the internet and social media.

Arguably, no historical phenomenon has been more culturally divisive, politically polarising and socially disruptive – including the Reformation, the French and Russian revolutions and both world wars.

The products of our highly connected age are dysfunctional societies influenced by right wing populism and left wing dogmatism. In the USA there is also the religious far-right, but more on that shortly.

Internet-dispensed populism developed muscle mass in the hot-house of the UK’s Brexit referendum in 2016 before sweeping Donald Trump to his first term as US president the following year.

For those clinging to the belief that objective reality still existed, the idea of non-politician politicians in government seemed crazy. Yet here we are, many years later, none the wiser and all the more guileless.

In 1984 one of the biggest obstacles to Winston Smith’s insurrection was the apathy of the ‘proles’ – in many ways similar to Karl Marx’s lumpenproletariat, or underclass. Since 2016 social media has mobilised large sections of what political analysts call ‘low propensity’ and ‘low information’ voters. These are individuals who have traditionally been unengaged and uninterested in the electoral process. They rarely voted and had limited understanding of the issues being contested.

Put simply, Facebook and Twitter in the hands of populist propagandists have achieved what Winston Smith and Karl Marx could not. In 2016 and 2017, social media ads, sharply focused on these sections of the British and US electorates, successfully got them to the polling booths in large numbers for the first time.

Anyone who doubts that the human mind can rationalise anything need look no further than the likes of Donald Trump and his British counterpart Nigel Farage, leader of the hard right Reform UK party and widely tipped to be the next British prime minister. His 2024 general election victory in the Essex constituency of Clacton-on-Sea led to his derisive moniker of the ‘Messiah of Clacton Pier’.

The irony of their success is delicious. Although both are from backgrounds of wealth and privilege, they are seen by their typically deprived devotees as ‘one of us’ and ‘not like other politicians’. This, of course, is because they are not politicians at all, at least not in the sense of being time-served public servants and longstanding members of traditional parties. However, both Trump and Farage have other attributes. Both are maestros of the Dog-whistle Philharmonic Orchestra, neither troubles himself with what we can learn from history or what research tells us, instead proffering simple solutions to complex and nuanced problems.

These two privileged white men are aided by sections of supporters who are enthusiastically credulous and determined to project their angst and anger onto the personas of their respective showmen. The topics of nationalism and immigration are without doubt their biggest draw.

So what about the dogmatic left? Terms like ‘woke’ and ‘politically correct’ are misleading and pejorative – and in any case have been co-opted by people who are neither. There is, however, a species of intolerant left wing orthodoxy with values perceived as universally binding. The penalty for those who do not subscribe to a certain world-view is cancellation, a one-way ticket to Coventry and the taint of being some sort of reactionary.

Of course the ‘cancel culture’ is nothing new. In the 1970s, ‘no platform for Nazis’ was a common clarion call among the far left. I disagreed with this then as I do now because you can’t have free speech with the caveat that it applies only to those you agree with, although this is an approach favoured by Trump and Farage.

What bothers me more is the notion that everybody is – or should be – morally obliged to support a set of diktats, especially in the toxic morass of identity politics.

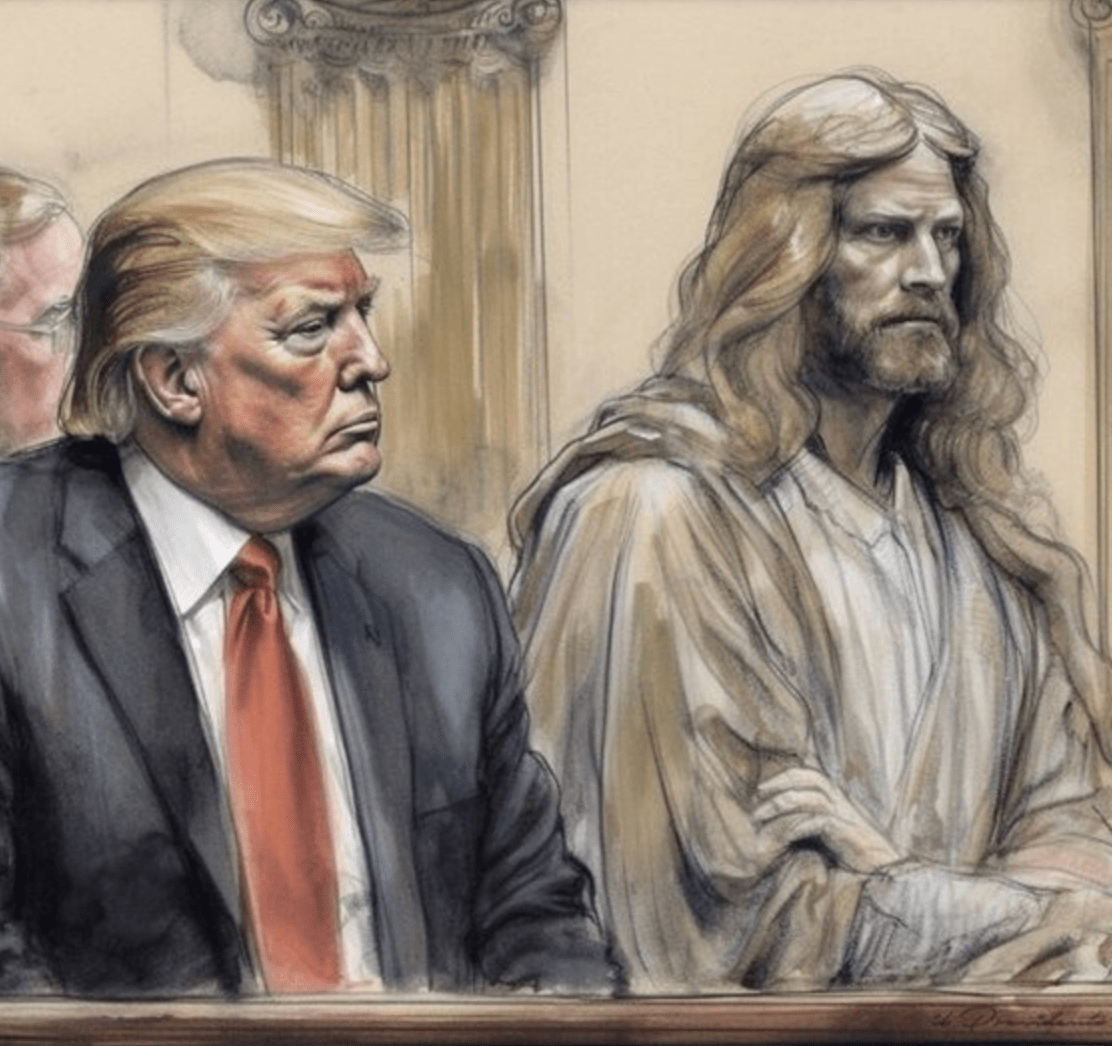

A sketch that appeared on social media of Donald Trump in court with Jesus at his side, as imagined by a supporter from the religious right

Unlike the ‘no platform’ stuff, this is new. As a student I was a punk rocker and considered myself an anarchist. But I didn’t want everyone else to be. Just the opposite. The idea of my dad’s generation wearing drainpipe jeans and torn T-shirts held together by safety pins, while spouting quotes from Proudhon or Bakunin would have appalled me.

In addition, unlike the rest of the west, America is home to various brands of Christian conservatism that provides a rich seam of support for Donald Trump and means the USA can add far-right theocrats to its mix of right wing populism and the dogmatic left.

In 1986 the American musician and satirist Frank Zappa said on TV, ‘The biggest threat to America today is not communism, it’s moving America toward a fascist theocracy.’ Zappa’s concerns were dismissed by the political pundits on the show with him and sadly, he died in 1993 aged 52 without living to see his prophesy fulfilled.

These days far right theocrats are enormously influential in America in a way people in other, largely secular western countries struggle to understand.

Televangelists who earn vast sums of money from people who can least afford to give it have been around as long as television. However, their shows have gained significantly more traction since the arrival of social media and the internet.

In a 2018 video appeal for cash donations, televangelist Jesse Duplantis said that if Jesus were alive today, he wouldn’t ride a donkey. Instead, he would use a facsimile of Air Force One to get from one preaching point to the next as fast as possible so that he could save more souls. This reasoning was used by Duplantis in his bid to raise funds for a $54 million private jet to ‘support’ his ministry.

Then, of course, there are Creationists whose first article of faith is that God made the earth exactly as described in Genesis and did so 6,000 years ago, complete with dinosaur fossils and everything else that we mistakenly believe pre-dates 4,000 BC.

Next one must consider Christian nationalists – what Zappa would call fascist theocrats – whose torchbearer is the formidable Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene. Their bedrock belief is that the USA was founded by Christians for Christians. Their kissing cousins are Theonomists or theocratic Christians who want Old Testament red-meat justice as well as religious leaders in government positions. There are also Seven Mountain Mandate-ists, Christian supremacists, Christian fundamentalists and dominionists. The list goes on. And on.

The Big Happy parodies each of these extremist groups by imagining a world under their rule – one third of the planet by right wing populists, another third by dogmatic leftists and the final third by fascist theocrats. It’s a weird and scary yet funny place. And despite being set in the far future, has a strangely contemporary feel.

Could it ever happen? I hope I’m wrong but I fear so.